When I met Anna Spargo-Ryan, she let me in on a secret in which every emerging writer will take comfort:

“The reality of writing is that maybe one day out of every five days, or every twelve days , or every 400 days, you feel inspired to write, and you feel like everything you write is amazing, and your muse is there and everything’s flowing through you. Most of the time, most writers mostly don’t feel like that, but new writers feel like they should feel like that otherwise the work won’t be good and so they wait to feel like that before they don’t any writing, and then if they don’t feel like that, they feel like they can’t call themselves a writer, and therefore will never be a writer. Like there’s a magical element to it. There’s a thought that you have to be a wizard to write and it’s a magical thing that’s bestowed on you at birth, ‘You are a writer with a Capital W.’ A lot of writers feel imposter syndrome well into their careers”.

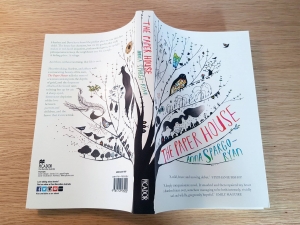

Even if Anna feels like an imposter, evidence certainly points to the contrary. Her first novel ‘The Paper House’, drawing on her own experience of mental illness will be released from Picador on May 31.

Despite being an experienced blogger and freelance writer, Anna was surprised by the lengthy nature of publishing: “Everyone says publishing is a really long process but until you do it, you sort of don’t fathom how long they mean. I signed my contract two years ago.”

The story was written during NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) 2013. At first, Anna had what would be considered a dream run for any author. She e-mailed it to an agent with whom she had corresponded regarding a previous project. The agent loved it, and signed her the next day on a two book contract. “I thought, ‘This isn’t slow! What are all these people talking about? This is easy!”. The book rights were sold to Picador five weeks afterwards. The reality of the publishing process then set in. The editing rounds took about five months , due to an editor on maternity leave, a commissioning editor on leave, another editor who left their role, an agent who quit agenting, then an inherited agent who had to get up to speed with her book. Anna describes a structural edit as editors looking at the entire story and saying: ‘”Here’s all the ways you can make it better, so here’s where your character’s aren’t as strong as they could be, here’s where the story doesn’t make a lot sense, here’s a plot bit that you’ve started and forgotten to continue”‘. During this process, she wrote 200,000 words for a 70,000 word novel. Once the editing was completed, it once again happened very quickly. In January, Anna received a call to say the novel had been accepted and would be released in June. “Maybe it says something about how slow publishing is that six months away seemed soon. I thought, ‘Are you sure? That’s this year! Oh God!'”

After the solitary and time-consuming nature of writing, the typesetting, cover design and getting a publicist from the publisher was quite a team effort:

“… I went from really having very little communication about it… getting the note and then going away and working on it and then sending it back, to being quite collaborative where I would get some notes from my editor and then the same day I would e-mail back and say ‘What if we did this?” then she would e-mail straight away and say, ‘What if we tried it like this?’ and it became quite a two-way kind of thing to get it finished at the end, which was really quite different from what the rest of it had been.”

As a writer who has now developed into a first-time author, how does Anna reflect on the editing and publishing period: “It was a really affirming process but terrifying and really hard word, it was such hard work.”

For many writers, releasing a novel to the masses is the equivalent of winning a gold medal in your field. Yet writing is a very personal activity; the tangible product of one’s own creative forces and innermost thoughts. How then, does Anna feel about her personal project being made available in bookshops and put in the hands of the public?

“I’m terrified, I’m so afraid. I write quite a lot and people sometimes have negative things to say about what I’m writing, but I’ve only put in three or four hours of work into an article or something and so when someone comes back and says ‘I don’t agree with what you’ve said or this is bad’, it’s not so devastating, but I’ve put four years of work into this.”

Anna’s philosophy toward criticism echoes the sentiments of all authors to which I have spoken:

“I really appreciate and enjoy constructive criticism because it helps me to learn, and to do things differently and better next time, but at the same time, I’ve got two daughters and I feel like it would be a bit like if someone took one of them and told me all the things that were wrong with them. There’s a lot of me in [the novel] and a lot of childhood dream stuff is caught up in it. Six year old Anna is there going, ‘We did it’ and I’m going, ‘But what if everybody hates it?'”

How will Anna judge whether The Paper House has been a success?

“Signing with an agent felt like success briefly and then getting it published and then finishing it. Commercial viability is not my aim with it at all, I have always wanted to strive for critical success rather than commercial. So if people appreciate it as a piece of work that will be success for me. I know it matters to my publisher, but it doesn’t matter to me whether it sells a lot of copies, as long as the people that are buying them think that it’s worthwhile. It’s a book about mental illness so the success of it is going to be how truthful people think that it is and whether it is a fair and truthful representation of mental illness, whether I’ve said something new about mental illness. One of the people who has read an early version of it said to me that they see so much of their own experience with depression in it, and that for them, that has been really confronting but that they haven’t seen that representation before. That’s really what I think will make me feel it’s been successful : Do people feel like I’ve done a good job in helping to promote the reality of mental illness…?”

What does Anna do about the fear some writers have that their work won’t be well-received, which can paralyse them into not writing at all? Write in spite of fear:

“You’ve got no way of knowing how people will respond until you do it, so there’s just a risk involved in getting the starting stuff done. When I started writing, I was very caught up in what people would say about it, especially that they would think I was a bad writer on a sentence basis. That they would read the writing and go, ‘Oh, the point she’s making is pretty good I guess, but the writing is not very good'”.

Don’t expect to write the perfect sentence straight away. Sometimes you have to write one hundred sentences before you find one with which you are pleased:

“Allow yourself to be bad, if you have to start from standing, then your writing is not going to be magic. If you get a run-up, then by the time you get to the part where the writing has to be amazing, you’re already warmed up. It is like a muscle and once you’ve warmed it up, it starts to flow more easily.”

Blogging is a good way of dipping your toe into the writing world, Anna says:

“I could just put something out that I didn’t necessarily think anyone should pay for, or that should be published, but that I wanted to say, and that was a good way for me to gauge how people felt about the stuff I was writing and it was quite low-risk. It was a good indicator of what I could expect if I put more and more work out. Like a fairly safe starting point, you can take it down whenever you feel like it. I still put on my blog stuff that I don’t think is worth publishing anywhere else.”

It is a common way of introducing yourself, creating an on-line presence and displaying a portfolio of work: “[You announce]here’s what I am as a writer, here’s what I have to say and you hope that it will resonate with people.”

So, what kind of writer is Anna?

“A lot of the time the characters do come to me at once, fully-formed. I don’t know what they’re going to do yet, not as a person who has a story or what it is or how to figure it out, but there’s something in it and I’ll see where it goes. I find it to be less like a job, it’s not my job solely, and I don’t whether that impacts on the way I feel about it, but I do feel more like there’s an instinct or intuition element to it -‘Who is this person, what have they got to say, how am I going to communicate it, what is the best way to write it down’ – and I often have to build a story. The character part I find quite easy and that’s the part I like, I really like people and learning about people and watching the way they interact with each other. But the ‘what are they going to do now?’ is particularly challenging. Elizabeth Gilbert has a TED Talk about ‘The Genius’ and grabbing ideas as they rush past, being able to transfer ideas from one person to another via touch and I really like the idea of that. There have been bits of writing that, I feel, have just arrived from nowhere and been a full concept and I’ve written it down and thought, ‘That’s done, that’s finished, that was the best way I could write it and now it’s gone’. I do a lot of life writing, memoir, and creative non-fiction, and the very difficult parts of that are expunged from me once I write about them. If I write about something that was very difficult in my life, once I write about it in the best way I can, I find it very hard to write about it again.”

For a writer whose interest and strength lies in character development and human interaction, who are her favourite fictional characters?

“The Eye of the Sheep by Sofie Laguna is amazing, one of the best books I’ve ever read. There’s a little boy in that and he is one of the best written characters I think I’ve ever read. Sofie has been able to make your heart go out to him, he pushes on to his outer limit through this immense suffering he’s experienced and he has a child’s naivety. It’s a really interesting comment on the power of humanity. Chris, from Emily Maguire’s new book An Isolated Incident. Her sister has been murdered, but instead of being a murder mystery which it isn’t, or being a very self-reflective character, she’s written this very tough, ‘pulls no punches’ type of woman who has sensitivity to her. She is such a nuanced character, I’m staggered by how well Emily has got this woman down on paper that had so much about her you could feel it happening away from the page. You could imagine what kind of person she would be away from the page.”

The idea that stories come to writers with ease, that they are slaves to a compulsion, is generally a misconception. Anna, who is studying her graduate diploma in creative writing cites having deadlines as helpful for her writing:

“If I only wrote when I felt like it, I wouldn’t ever finish anything. If I’ve got a reason why I have to, then I will get it done. Sometimes I just want to watch TV or go to bed, or think other writers are so much better than me.”

Remember your writing is never as bad as you think, and you are not alone in any feelings of inadequacy you experience:

“Charlotte Wood talked in her Stella award-winning speech about how she thought it was hopeless, and she wanted to give up and stop writing, and it’s an amazing book! Do as much as you can to realise that’s a normal part of the writer experience – you will go through periods where you feel like your story is the worst writing that has ever been. [There will be]cycles of despair or elation, it’s normal. If writing is well intentioned and the hard work has gone into it, and you’ve taken on board other feedback, it usually is worthwhile.”

On Anna’s website, she often writes book reviews. There is a common theme of feminism, so what is Anna’s take on the recent ‘I don’t need feminism’ backlash:

“At the moment, there seem to be two clear streams of feminism. One of them is almost ‘post-feminism’, in the sense that it isn’t following the same approach to feminism as our mother’s generation was doing. There’s another one which does continue that kind of thinking. I am not a supporter of aggressive feminism, I like a lot of the people who are doing it as people, but I can see why there’s push-back against it, not just from men but from other women who are going,’You don’t represent me and my ideas, and these ideas aren’t what I’m about.’ I think that’s alienating and I think it works against the idea of feminism, to alienate feminists.

I don’t think feminism is the same as equality. I think there are a lot of issues within the feminist history that need to be considered, as well as, ‘We want to earn the same money, same benefits, equal representation in the workplace’, and all these things, but it’s also considering all the things that have happened to get to this point in women’s history, and I think that gets left out a bit now. Maybe we take some of that stuff for granted and don’t incorporate how we got there into the way that we approach feminism. In that sense, I don’t think we are capturing the whole of feminism into the activities that we are doing. What we end up with is not all the people that could be engaged with feminism, because they feel like their idea of what it is to be a woman, is misaligned with some of the louder voices and therefore they shouldn’t be included in it, or they don’t want to be part of it. It’s a scary thing to talk about because there are so many different opinions. Mental health is like that.On the podcast, we talked about Stephen Fry and his lack of intersectionality. I think that in promoting loudly one particular element of the cause, a lot of the nuance is lost and a lot of the understanding of how all the different people within that discourse interact with each other is missing, where you get a lot of loud feminists for example – and it’s not limited to feminism – who don’t understand the role of race, or ability, or socio-economic status in feminism….I find that problematic, it’s about the consolidation of all different experiences, some of them need different treatments, and I don’t know that this other stream of feminism is very god at thinking about that… but I’m willing to be proven wrong!”

With this interest in feminism, it perhaps follows that Anna looks up to a woman who “busts the glass ceiling a lot”:

“My mum is a really inspiring lady, it sounds really trite but she was the first woman to chair a financial institution in Australia. She’s now a full-time non-executive director. She’s one of only I think ten, it might be nine, women who chair ASX200 boards. She works a lot in male dominated industries. The board she chairs is an engineering firm, she does other science-related things, such as financing. Every day she faces sexism in the workplace, and misconceptions about what it means to be a woman in these industries. Whenever I’m feeling like ‘I don’t know why you would bother going on’ or that its futile or it’s not fair, I just have to speak to her for five minutes. She puts it in perspective not only because she does all these things, but also takes the time to talk to me about it. Here’s a woman who does all this amazing stuff but is still wonderful enough to bring comfort and inspiration to her children and other women as well. She does lots of mentoring things, so it’s nice to have a built in fairy godmother like that.”

Did Anna’s parents imbue her with a particular belief system?

“My dad’s family and mum’s family are quite religious, my dad has, I think, three cousins who are ministers or reverends. He was a Sunday school teacher but he was very critical of biblical teaching. He’s an engineer so he’s a very maths and science brain guy, and some of the logical fallacies in The Bible, I think he found them difficult. He got booted out of Sunday School because he refused to teach ‘Thou shalt not kill’, and David and Goliath. [He said] ‘I don’t understand how these two things go together, this isn’t what I understand spirituality to be’. I think that’s kind of the household I was raised in, where you can be critical of things, including religion. I went to church a few times and had a kind of religious experience when I was in Rome (I think everyone does!). I went to the Basilica and kind of felt this wash of religious inspiration flow through me but it didn’t last very long! I’m generally spiritual in that I believe in intuition and general connection to the earth and connection to time. I’m not an existentialist, I don’t believe that we’re just here for a while and then we’re gone, but I don’t know what I believe instead yet. I feel like I’m a fairly spiritual person but not in an organised way.”

Anna heavily relies on her intuition when making decisions:

“I mostly go on gut feel, I’m a big believer in gut feel, and that’s mostly come about after years of being a freelancer and having gut feelings about clients and thinking ‘I shouldn’t take that on’ and every time I’ve thought that, it turned out to be horrible. After four or five years of that, I thought, ‘Why am I not trusting my instincts on this?’ … It took me a long time to realise those feelings I had were warning signals. If you feel hesitation, then it’s probably not a good decision. All the decisions that I’ve made against my gut have turned out to be wrong decisions. That’s affirming in its own way, like I can trust myself.”

Which decision did Anna make to set her on the writing career path?

“I had a very deliberate moment where I was working in local council and an opportunity came up to work for the Australian Grand Prix Cooperation. The pay was crap, I had to take a pay cut and the work was really hard, and the hours were very long. I thought at the time, ‘This is how I am going to change the way that I can work. and the people that I know, and the industries that I am qualified to work in, I need to take this to push my career in the direction I want it to go in’. That was a very deliberate choice and at the time I thought, ‘I don’t know whether this is going to pay off’, but it was worth the risk.

Before working at the Grand Prix, I got told, ‘You’ve been a developer for small businesses and local governments and state governments’, but nothing that was very compelling to people. After the Grand Prix, it was so much more in line with what I was hoping to do. I worked at Neighbours for two years and that was my actual dream job. That was my dream job before I ever saw it advertised. I just saw it on LinkedIn. They had been interviewing for four months I think, and hadn’t found anyone they liked. Somehow I fluked getting an interview but once I got it, I really put a lot of thought into how I would approach this job. I went to the interview with a lot of ideas and hoped for the best, and hoped that my love of Neighbours would get me through as well . It did and I was thrilled and it was so fun, but I don’t feel like I would have been able to get their attention if I hadn’t also worked at Formula One. It was just that kind of job where if you can work on social media in the pits until 1am, and it’s all good content and you engage a lot of people and you grow a big audience, then you’ve proven you can do the job well.”

Anna’s blog is quite personal, so is there any material or aspects of her life which are off-limits?

“I used to write about my children a lot more than I do now, that’s partly because they’re nearly teenagers and I don’t feel like they are my story to tell any more. If they want to tell these stories they can, not now! [I won’t write about] anything that is going to potentially jeopardize the reputation of someone I care about…but if it’s mine, I don’t really have any limitations on what I’ll write about. The stuff that is the most private, especially the mental illness stuff seemed to have been of the best value to people.”

What gave Anna the courage to first write about her experience with anxiety and depression?

“I was so depressed, I thought, ‘I don’t know of anything except being depressed right now, so I’ll write about that’. It was really scary at the start, but then it opened up a community of people who felt similarly and who really got something out of someone writing about it in a way they could then share with friends and family…that was very rewarding. It had value outside of me just talking about myself (which I love to do!). I thought ‘Am I just being really self-absorbed?’ (which is probably true as well!) but it seemed to help people….”

On April 30 2015, the first episode of The Anxiety Shut-In Hour was released. It works to remove stigma around mental illness and increase understanding of health by talking about its representation in media, literature, pop culture and society in general. The project is the manifestation of a dream that Anna’s co-star, lawyer Anna Van-Krimpen had:

“We had dinner one night and that was the only time we had met. She tweeted me and said ‘I had a dream last night that we started a podcast and it was called The Anxiety Shut-In Hour’. I said, ‘Why don’t we do one?’ It’s a terrible name and a horrible thing to say about anxiety, but you have to laugh at yourself about it. It is really fun, nice to be able to talk openly and frankly and with humour about what living with anxiety is like, because it can become completely overwhelming. ‘I’m so worried all the time, I’m so fearful, I’m so sad’ so to be able to talk about it in a way that touches on all those things, but also, ‘We’re having a good time right now, we have strong opinions about how anxiety and other mental illnesses are presented in society and in the media and government’. … it was comforting for people to listen to something about their life without being weighed down by how awful everything is.We get really nice feedback about it. A lot of it is from people who haven’t come out about their mental illness yet, people who don’t feel like they can talk to others about their anxiety who appreciate it because it feels like having a conversation with us. It’s led to some other things, I’ve written about it, I’ve been on the radio, its been a different approach to talking about mental illness from what has been in the media before (in this country anyway!), where people haven’t spoken openly about mental illness in a very constructive way. It feels like a constructive conversation and not just self-loathing, but actually ideas for how to improve the state of mental health support in Australia.”

How does Anna explain the feeling of having anxiety?

“The only way I’ve managed to describe anxiety is through metaphoric language. It’s so irrational that trying to put rational words around it is quite difficult. It does feel like you’re going to die, but if someone doesn’t know what that feels like, it’s quite hard.’I feel like I can’t breathe, my chest is really tight, I feel light-headed’, all these physical symptoms, but it’s not quite like that. I know that I can breathe, but I feel like I can’t. The most recent way I wrote about it was in an article I wrote for The Guardian which was about feeling like you’re going to float away and being suffocated by anxiety. That was really widely read and I got a lot of e-mails from people who said they hadn’t been able to describe it to their family before. Metaphoric language allows you to put relatable words around an experience that is different for everybody. It allows for a broad spectrum of experience.”

Anna says one of the most important ways a person can assist someone with anxiety is by understanding what will help them before the person starts panicking. If a person is having a panic attack, they often won’t have the emotional energy to tell you what they need. It helps if it is not made to be the person with anxiety’s responsibility:

“I had one boyfriend who was really good at breathing with me so if he saw that I was panicking, he would stand behind me, hold my body and breathe really deeply, and my body would sync with his. My current partner spots when I’m panicking before I know that I am and he does grounding things, tap my leg or squeeze my knee, something that helps me reconnect with the physical sensation. A panic attack for me is almost disconnecting from the physical world, I’m going to die, I’m going to pass out, things that are a break from reality.”

For Anna, this technique of not demanding answers passes on to her parenting style:

“A child psychologist once told me if you ask a child how their day was, you’re demanding an answer, it’s better to help them have words for the way that they’re feeling. Make suggestions or solutions ie. Did your day make you feel glad? That was a real revelation.”

With the podcast and her writing both having the theme of mental health, Anna wrote on her blog earlier this year about her tendency to write about ‘the sadness instead of the adventure,’ and the urge she sometimes feels to separate herself from this topic and write about her other interests:

“I contributed to From the Outer which is a book about football from people who don’t normally get a chance to write about it. I think writing that story made me realise how much I enjoy writing about other things as well, and I had stopped. I did feel that If I didn’t write about mental illness, people would be surprised. It’s been detrimental to my own mental health to only write about mental health. Sometimes it’s helpful but when it’s the only thing I’m writing on, it’s easy to feel like it’s the only factor of my personality and that it’s the only part of me people are interested in. I got to a point where the only contribution I felt I could make which was different or better to what other people were doing was in mental health. I’ve made a deal with myself not to write so much about it this year because I’d like to see what else I can do.”

Anna has the next three months off to write her next novel:

“That’s a book about family violence. It’s fiction but it’s about how family violence impacts the children. There’s a little brother in the story who is just the sweetest kid and it’s very difficult to not get tied up and protective while I’m writing the story. It’s quite different from the first book, which is magic realism, poetic and metaphoric language. The second book is much more real and probably more confronting, more of a reflection on the way society sees family violence, whereas the first book is more about how individuals see their own mental illness and the hereditary nature.”

After that will come a memoir:

“I don’t know whether I’ve got enough to say so it’s coming together very very slowly. Writing about mental illness so much gets really boring where I think I’ve said it all, I feel like I’ve given a complete representation of what my experience is like, maybe I don’t need to keep writing about it over and over and over. That’s going to come from understanding if it’s helpful for other people if I do.”

What does the future hold for Ms. Spargo-Ryan? It seems like Anna, who is respected by critics and loyal readers alike, is being very humble when she tells me the hopes she has for her career:

“My end goal is probably write novels and teach writing and if I can have then enough time and income to experiment with other kinds of writing, that would be ideal.”